Campus Medius – Digital Mapping in the Humanities

This text derives from a lecture given by the author at the University of Vienna on 25 April 2018. A preliminary, German version of the article was published in Ingo Börner, Wolfgang Straub, Christian Zolles (eds.), Germanistik digital. Digital Humanities in der Sprach- und Literaturwissenschaft, Vienna, Facultas, 2018, pp. 104–117. All 20 figures are available here.

I. Topography: Campus Medius 1.0

This article explores digital mapping in the humanities based on the research project Campus Medius. The first chapter presents the initial version of the website campusmedius.net, which I developed in collaboration with the programmer Rory Solomon and the designer Mallory Brennan at the New School in New York, and which has been online since 2014.1The project was supervised by Shannon Mattern, who has since published her “urban media archaeology” in two books: Deep Mapping the Media City, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 2015; Code + Clay… Data + Dirt. Five Thousand Years of Urban Media, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 2017. Most of the HTML, CSS and JavaScript programming was done by Darius Daftary. The idea for the project originated in my doctoral studies on the media references in the writings of Karl Kraus (1874–1936) and Peter Altenberg (1859–1919),2Cp. Simon Ganahl, Karl Kraus und Peter Altenberg. Eine Typologie moderner Haltungen, Konstanz, Konstanz University Press, 2015. where I investigated a text that Kraus had written in Vienna in 1933: the Dritte Walpurgisnacht.3Cp. Karl Kraus, Dritte Walpurgisnacht, edited by Christian Wagenknecht, Frankfurt a.M., Suhrkamp, 1989. In this 300-page essay, the events of a weekend that May are central to its critique of the contemporary political situation (i.e. the Nazi “seizure of power” in Germany and the Austrian response to these developments). By researching what had happened in Vienna on 13 and 14 May 1933, I soon understood why Kraus had experienced this weekend as a turning point. Consequently, I decided to digitally represent 15 selected events within 24 hours, from Saturday at 2 p.m. to Sunday at 2 p.m., on a map of Vienna from 1933.

The selection of the empirical material was also influenced by the concept of the chronotope. In the 1930s, Mikhail Bakhtin had written an essay on time-spaces or space-times in literature from antiquity to the Renaissance, which became very important in literary studies after its publication in 1975.4Cp. Mikhail M. Bakhtin, “Forms of Time and of the Chronotope in the Novel” [Russian 1975], in Mikhail M. Bakhtin, The Dialogic Imagination. Four Essays, edited by Michael Holquist, translated by Caryl Emerson and Michael Holquist, Austin, University of Texas Press, 1981, pp. 84–258. His approach inspired us to limit the historical corpus to exactly 24 hours in Vienna – a temporal and spatial unity that not only emerged in the course of events, but also resembles the most significant chronotope of the modernist novel. Just think of James Joyce’s Ulysses, Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway, Andrei Bely’s Petersburg or – to name another medium – the documentary Berlin: Die Sinfonie der Großstadt by Walter Ruttmann. In all these artworks from the first third of the 20th century, one finds the attempt to capture modernity in a very specific time-space: a day in the city.5Cp. Simon Ganahl, “Der monströse Fouleuze. Eine philosophische Lektüre von Andrej Belyjs Petersburg”, Le foucaldien, 3 (1), 2017. DOI: http://doi.org/10.16995/lefou.23.

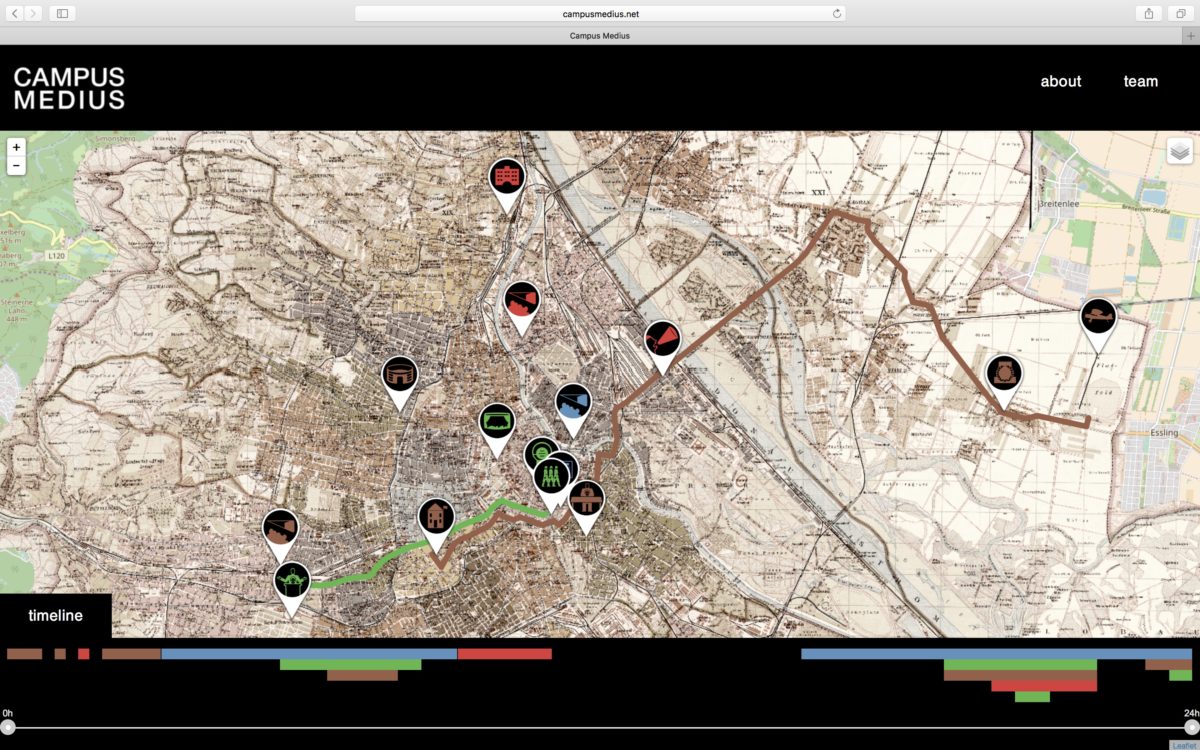

On campusmedius.net, users can discover what was happening simultaneously at different places in Vienna by moving the 24-hour timeline. [Fig. 1] For example, on Saturday evening, 13 May 1933, the Burgtheater staged the play Hundert Tage, which was co-written by Benito Mussolini; several cinemas screened Fritz Lang’s sound film Das Testament des Dr. Mabuse; in the Engelmann-Arena a National Socialist rally was held; and a small movie theatre near the Friedensbrücke hosted a Russian film night. [Fig. 2] The map also makes it possible to give a spatial overview of the selected events. [Fig. 3] However, we not only geo-referenced their sites, but used an established technique for historical mapping projects that is called rectification. [Fig. 4] In our case, a city map of Vienna from 1933 was scanned with high resolution at the Austrian National Library, then converted into a GeoTIFF-file and finally rectified to align with the underlying GIS data of OpenStreetMap. This rather banal matter discomfited me because of the idea that a digital map represents reality from which a printed map more or less deviates. What actually happens in the process of rectification, though, is a translation between different projections of reality that can and should be traced back to the historical conditions of their emergence.6Cp. Todd Presner, “The View from Above/Below”, in Todd Presner, David Shepard, Yoh Kawano, HyperCities. Thick Mapping in the Digital Humanities, Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 2014, pp. 84–127, here: pp. 110–118. Mainly due to my scholarly discontent with this cartographical approach, we now strive to question and alienate these standardised representations of time and space in an entirely revised and substantially expanded version of the website that I will discuss in the second chapter of the article.

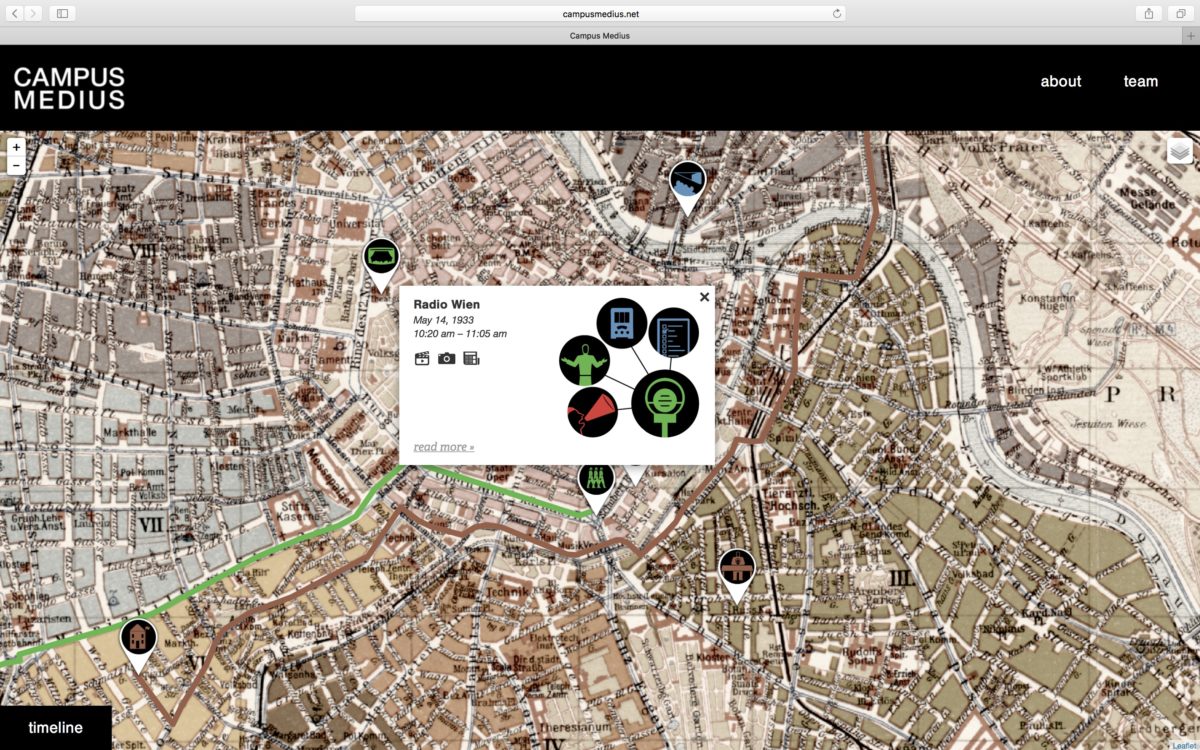

By selecting a pin on the map, an actor-network of the respective event pops up. [Fig. 5] Methodologically, this visualisation is derived from actor-network theory, which basically states that it is not a human consciousness that decides to act, and then things happen accordingly – in other words, that actions should not be understood as human intentional, but rather as interplays between human and non-human actors.7Cp. Bruno Latour, Reassembling the Social. An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2005. Regarding the exemplary event on figure 5, a live broadcast of a political speech, certain microphones and radio sets, leader figures, protests and questionnaires made differences in the course of action. The colours of the icons designate political backgrounds, with red for socialist and communist, green for Austrofascist, brown for National Socialist and blue for bourgeois actors. If the user clicks on this window, a scholarly description of the associated event opens up, featuring photographs, sound recordings, movie clips, archival documents, press articles, etc. [Fig. 6]

This is, by and large, the first version of campusmedius.net as the website went online in 2014 – a kind of digital exhibition. The project’s take on digital humanities has been strongly influenced by the Digital Humanities Manifesto, which argued for “the scholar as curator and the curator as scholar”8The Digital Humanities Manifesto 2.0 (2009). Available at: http://manifesto.humanities.ucla.edu/2009/05/29/the-digital-humanities-manifesto-20 [accessed 30 June 2018].. With every historical document that is digitised, this claim becomes more important. By 14 March 2018, the Austrian National Library, for example, had made 20 million newspaper pages available online: what is such ‘big data’ good for if it is not correlated in meaningful ways?9Cp. ANNO (Austrian Newspapers Online). Available at: http://anno.onb.ac.at [accessed 30 June 2018]. One way is to develop algorithms in cooperation with software engineers; another way is to tell factual stories by employing material from the digital archives. We started with the latter approach, used the empirical findings to translate our methodological concepts into a data model, and have begun to devise an algorithmic analysis based on the historical case study that I will present in the following chapter.

II. Topology: Campus Medius 2.0

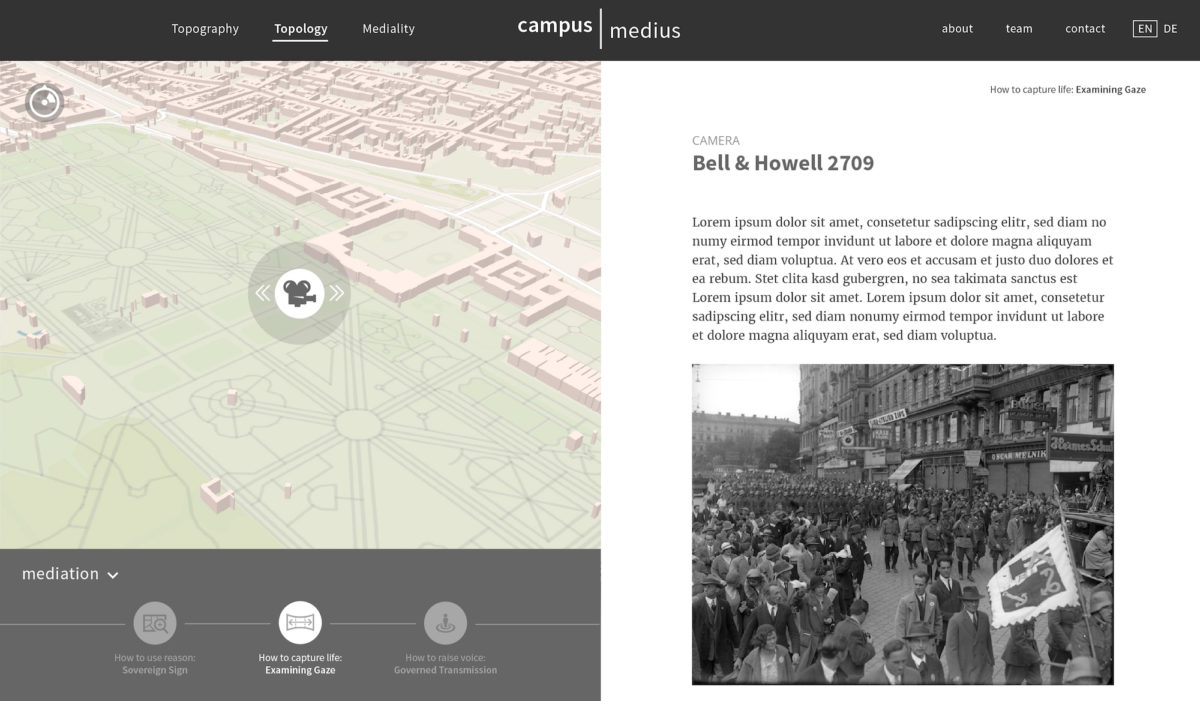

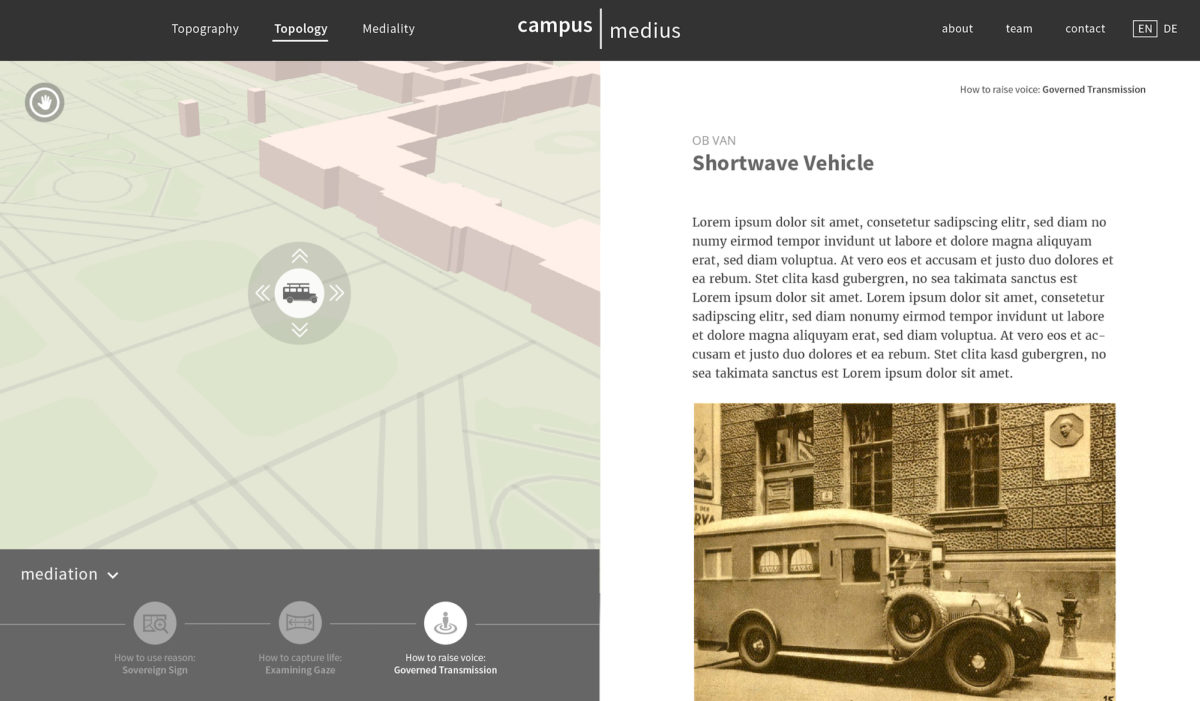

In the forthcoming version of campusmedius.net, this overview of the historical chronotope will continue to exist in the website’s “Topography” section, comprising as before the 24-hour timeline and the rectified map of Vienna from 1933. [Fig. 7] The 15 events, however, will only be marked by ordinary pins as the concept of the actor-network moves to a new section that we call “Topology”. In this area, we focus on the main event of the selected time-space: a so-called “Turks Deliverance Celebration” (Türkenbefreiungsfeier) held in the gardens of Schönbrunn Palace on 14 May 1933, which is narrated or rather correlated three times. The narrative technique of telling a story from different perspectives is very common in novels, films and especially serials. In the case of Campus Medius, this approach is deployed to construct ideal-typical interfaces meant to spotlight and denaturalise representations of time and space that have become standardised in digital mapping.

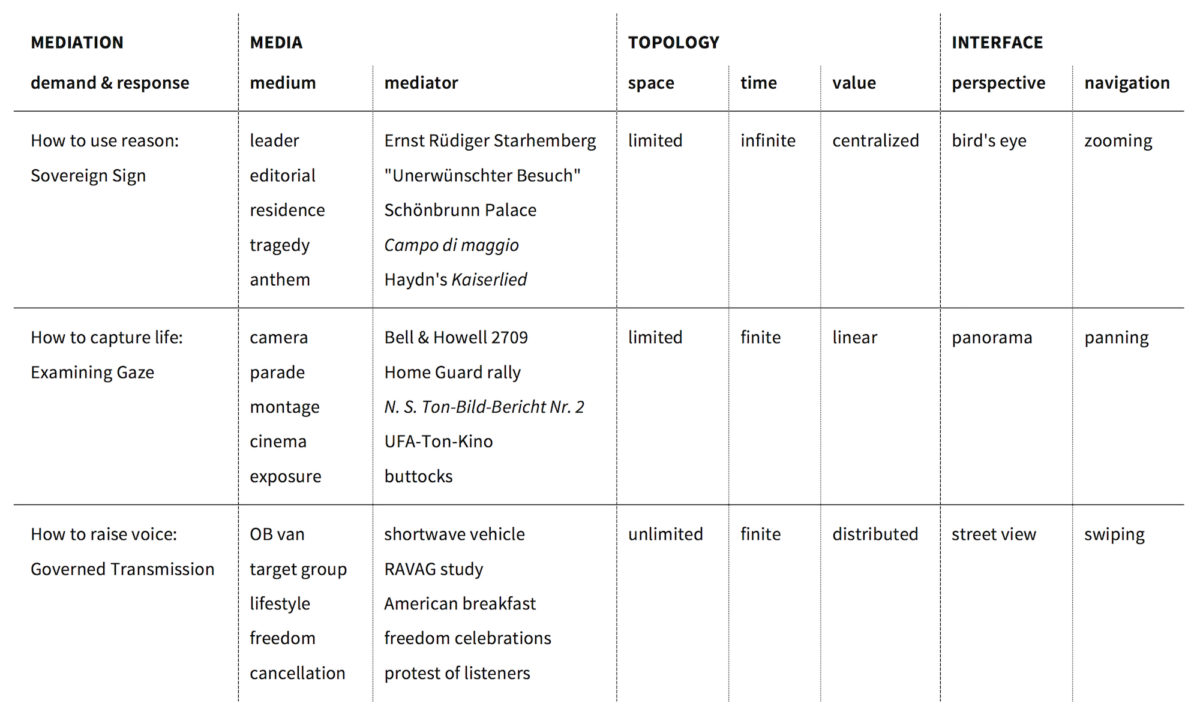

The table shown in figure 8 outlines our triple narration or correlation of the “Turks Deliverance Celebration”. [Fig. 8] Conceptually, the scheme is based on a question that has bothered me since the outset of the project: what is a media experience? Or more precisely, what does it mean to have a media experience in modernity? This line of inquiry derives from Michel Foucault’s studies of criminality or sexuality as modern forms of experience.10As Foucault wrote in retrospect, his studies of modern madness, disease, criminality and sexuality explored “the historical a priori of a possible experience”. (Michel Foucault, “Foucault”, translated by Robert Hurley [French 1984], in Michel Foucault, Essential Works of Foucault. 1954–1984, vol. 2, edited by James Faubion, Harmondsworth, Penguin, 2000, pp. 459–463, here: p. 460.) But can we also conceptualise mediality as an experiential field in the Foucauldian sense? What possibilities of having media experiences are opened up in modernity? The table answers this question with a bold thesis: having a media experience in modern societies essentially means using reason in sovereign signs, capturing life in examining gazes, or raising the voice in governed transmissions. These three possibilities of having media experiences – in Foucauldian terms: dispositifs of mediation – are expressed in heterogeneous mediators. As for the “Turks Deliverance Celebration” in Vienna on 14 May 1933, each mediation contains five mediators that are associated in specific types of connection, in distinct topologies. Are the mediators building territories or spreading in an unlimited space? Do they end sometime or potentially exist infinitely? Is a centralised or an equalised distribution taking place? Etc. The mapping interfaces result from these topologies, because seeing things from a bird’s-eye, panoramically or in street view entails certain mediations of the world, certain ideologies that we aim to elucidate.11On interfaces as practices of mediation, cp. Alexander R. Galloway, The Interface Effect, Cambridge, Polity, 2012, and Johanna Drucker, Graphesis. Visual Forms of Knowledge Production, Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 2014.

Before discussing an example of each mediation, I would like to elaborate on the design of the mediators that are, following actor-network theory, humans or non-humans making differences in a course of action. My current job is to precisely describe the “Turks Deliverance Celebration” from the standpoints of these 15 selected mediators, whose provisional icons are shown in figure 9. [Fig. 9] Mallory Brennan, the designer of the initial version of campusmedius.net, had already styled the icons along the lines of the “International System of Typographic Picture Education” (Isotype) – a conceptually universal picture language developed under the direction of the political economist Otto Neurath, a member of the Vienna Circle, from the mid-1920s onwards.12Cp. Otto Neurath, International Picture Language. The First Rules of Isotype, London, Kegan Paul, 1936. Susanne Kiesenhofer, who is designing our new website, has accordingly created icons for all 15 mediators based on Isotype, which we do not understand as a universal design concept, but rather as a visual vocabulary that is closely related to the historical setting of our case study.

So how will the new section “Topology” be implemented on the website? I start with the mediation “How to use reason: Sovereign Sign”, using the example of the mediator Ernst Rüdiger Starhemberg, the Federal Leader of the Austrian Home Guards (Heimwehr or Heimatschutz) and initiator of the “Turks Deliverance Celebration” in Vienna on 14 May 1933. [Fig. 10] Instead of a timeline, the Topology includes a slider beneath the map where users will be able to switch between the different mediations. In this case, the mediators are viewed from above and navigated via zooming. The network is centralised, i.e. all navigations have to pass a central node: the transcendent bird’s-eye, overarching the earth’s surface, which is not only the perspective of God, but also of the sovereign monarch overseeing his or her territory.13Cp. Presner 2014, pp. 84–101. This world view was very familiar to Starhemberg, who came from an old aristocratic family of the Habsburg Monarchy, which ended together with the First World War in 1918. One of his ancestors was Count Ernst Rüdiger von Starhemberg, the successful military commander of Vienna during the second Turkish siege of the city in summer 1683. Led by chancellor Engelbert Dollfuß, the Austrian government adopted an authoritarian course in March 1933. His cabinet prevented parliament from working and governed by emergency decree, but it was not clear that spring how things would continue. Supported by Benito Mussolini, Italy’s fascist prime minister, Starhemberg suggested holding a Home Guard rally to celebrate the 250th anniversary of Vienna’s liberation from the Turkish siege, which actually took place in mid-September 1683.14Cp. Ernst Rudiger Starhemberg, Between Hitler and Mussolini, New York/London, Harper & Brothers, 1942, pp. 95–117. However, the plan was to give a public signal of Austria as a fascist sovereign nation earlier in the year, and it worked out: on 14 May 1933, the chancellor swore fidelity to the leader of the Home Guards in front of up to 40,000 members of his paramilitary organisation, deployed radially in the Baroque gardens starting from the balcony of Schönbrunn Palace, where Dollfuß and Starhemberg were standing.15See, for example, the coverage in the semi-official newspaper Reichspost (Vienna), 15 May 1933, pp. 1–3. Available at: http://anno.onb.ac.at/cgi-content/anno?aid=rpt& datum=19330515 [accessed 30 June 2018].

In the second mediation, “How to capture life: Examining Gaze”, the users view and navigate the map panoramically. Its topology is linear meaning they need to pan from the first to the fifth mediator one after another. The example in figure 11 is the 35mm movie camera “Bell & Howell 2709”, which was famously used by Charlie Chaplin. [Fig. 11] I recognised the camera with its characteristic film magazine on the very right of the photograph included in the figure, which shows the parade of the Home Guards following the rally in Schönbrunn, captured here on Mariahilferstraße near Vienna’s western railway station.16The photograph is archived in the Bildarchiv Austria. Available at: http://www.bildarchivaustria.at/Pages/ImageDetail.aspx?p_iBildID=1553954 [accessed 30 June 2018]. On a high-resolution scan of the picture, we not only identified the model, but also realised that this unique camera had been equipped with an aftermarket motor and apparatus for recording sound. The reel was shot for the German version of Fox Movietone News and has survived in the Film Archive Austria.17Cp. “Die Türkenbefreiungsfeier des österreichischen Heimatschutzes in Wien”, Fox Tönende Wochenschau, VII/20, 15 May 1933, Filmarchiv Austria (JS 1933/8). I am particularly interested in the question of which kind of film this assemblage was able to shoot, how this specific camera made it possible to capture the movement of the parade. In a way, this upgraded Bell & Howell 2709 reviewed the paramilitary procession not unlike the members of the Austrian government awaiting the march-past at Schwarzenbergplatz in the city centre. And the spectators viewing the newsreel in the cinemas later on, are they not taking up a similar position of examining these moving bodies?

The third mediation, “How to raise voice: Governed Transmission”, is determined by the mapping interface of the street view. Here, the users can navigate in all directions, but will not be able to escape this narrow perspective. As a corresponding mediator, I lastly present the shortwave vehicle of the Radio-Verkehrs-AG (RAVAG), the forerunner of today’s Austrian Broadcasting Corporation (ORF). [Fig. 12] Such vans that allowed live broadcasts from outside the radio studio had been available in Austria since the late 1920s. In the case of the “Turks Deliverance Celebration”, the shortwave vehicle was employed to transmit the speeches held at the rally in Schönbrunn live on Radio Wien.18A short recording of the live broadcast has survived in the Österreichische Mediathek. Available at: https://www.mediathek.at/atom/136BBF40-225-02D1A-00000904-136AFAF1 [accessed 30 June 2018]. However, the transmission prompted more than 10,000 listeners to cancel their radio registration, because they wanted to protest against the usage of public broadcasting for party political ends.19Cp. “Die Antwort auf den Kikeriki-Sonntag”, Arbeiter-Zeitung (Vienna), 16 May 1933, p. 2. Available at: http://anno.onb.ac.at/cgi-content/anno?aid=aze&datum=193305 16&seite=2 [accessed 30 June 2018]. What these people express in collective letters of cancellation is an aversion to being patronised by the state and a strong will to raise their own voices. The protests correspond to the findings of a contemporary study carried out by the Wirtschaftspsychologische Forschungsstelle, based in Vienna and headed by Paul Lazarsfeld, who later became a major figure in American sociology after his emigration to New York.20Cp. Desmond Mark (ed.), Paul Lazarsfelds Wiener RAVAG-Studie 1932. Der Beginn der modernen Rundfunkforschung, Wien, Guthmann-Peterson, 1996. The RAVAG had commissioned this institute for economic-psychological research to run a statistical survey of the tastes of Austrian radio listeners. The innovative aspect of the study, which presented its findings in late 1932, was not only the quantitative measurement of listeners’ wishes, but above all the fact that it provided information on the likes and dislikes of various social groups. By correlating radio programmes with social data, the study broke down the mass audience into specific target groups. These are the beginnings of what is called ‘profiling’ today and what might be appreciated or rejected as management of the freedom to communicate in modern societies.

III. “The Database Is the Theory!”

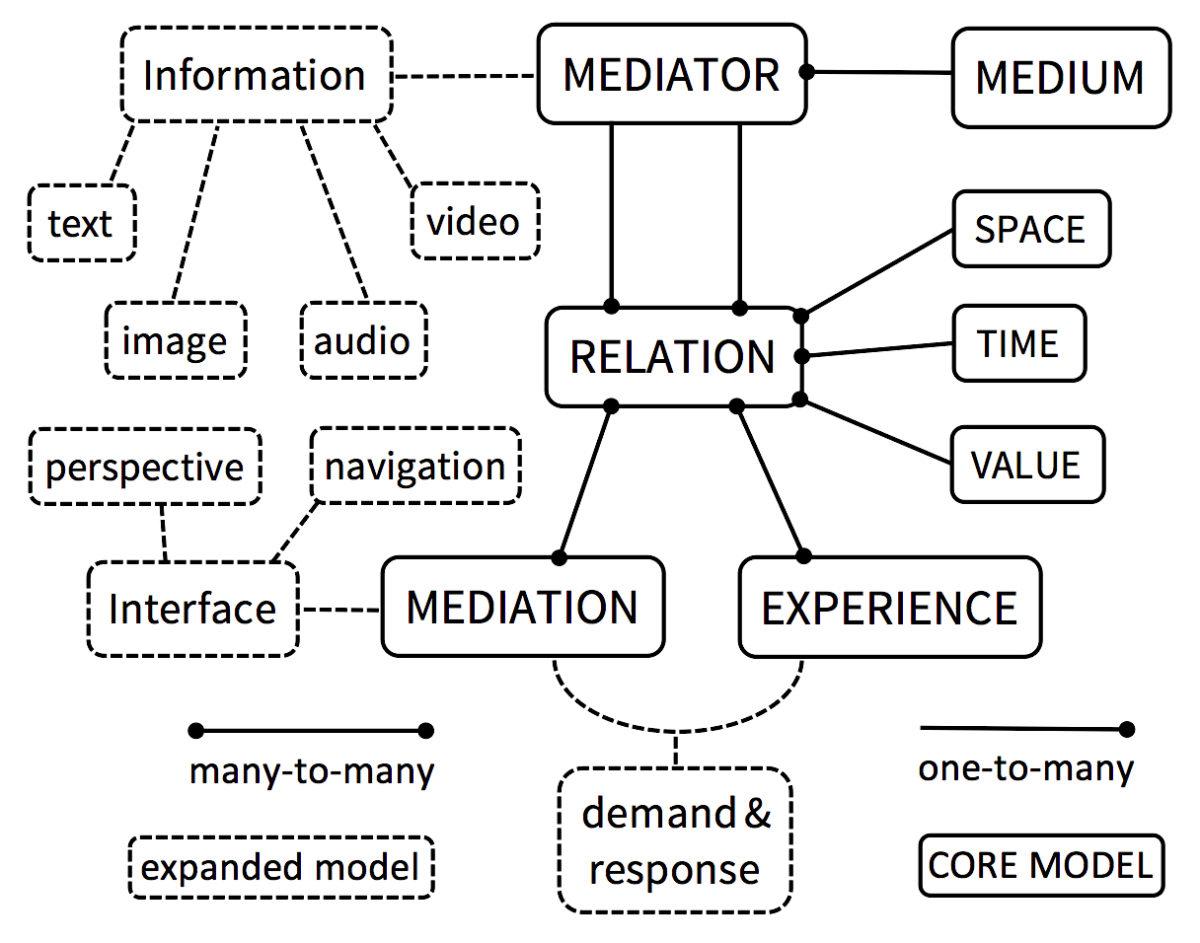

As I want to emphasise the methodological potential of digital mapping in this article, the third chapter will deal with the data model on which the forthcoming version of campusmedius.net is based. In the first two chapters, I mainly discussed the website’s front end, i.e. issues related to the interface. On the other side of the software stack, however, an intrinsically invisible back end is located, a database in which all the content is stored. What I would like to stress here is that deciding which entities are included in the database and how they are related is a genuinely methodological question. In order to build a database, the research approach needs to be operationalised – at least working definitions of the central concepts are necessary. In a project within the field of the humanities, this work can definitely not be conducted by software engineers alone, because: “The database is the theory!”21Jean Bauer, “Who You Calling Untheoretical?”, Journal of Digital Humanities, 1 (1), 2011. Available at: http://journalofdigitalhumanities.org/1-1/who-you-calling-untheoretical-by-jean-bauer [accessed 30 June 2018]. If we want a website to match up to the complexities of our theoretical approaches, both its database and its interface must be constructed in a truly interdisciplinary cooperation with programmers and designers.

Figure 13 shows a diagram of our current data model that I created collaboratively with the geomatics engineer Andreas Krimbacher, who has been the core developer of Campus Medius since 2015. [Fig. 13] We start with the entity at the top, the mediator as anyone or anything given in an experience that makes a difference in the course of action. In our terminology, a medium is none other than a type of mediators: Starhemberg appears as Federal Leader of the Austrian Home Guards on the stage of the “Turks Deliverance Celebration”, but ideally aligns himself with leader figures ranging from the Roman Caesars via the Habsburg emperors to the fascist Duce. This is an example of a one-to-many relationship, one medium comprises many mediators. It was important for us to attach the attributes space, time and value – the latter understood in terms of weighing the nodes in a network – to the relation, which connects different mediators, and not to the mediator itself.22The selection of space, time and value as relational properties is based on Foucault’s analysis of power relations, especially his precise description of spatial distributions, temporal orders and evaluative rankings. Cp. Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish. The Birth of the Prison, translated by Alan Sheridan, New York, Vintage Books, 1995 [French 1975], pp. 135–228. The common practice in digital cartography, however, is to determine where and when an entity occurs, i.e. to set its location (latitude/longitude) and its date and time. Yet this approach would have required a kind of transcendental gaze, an external perspective able to situate mediators in absolute time and space. In order to avoid this “god trick of seeing everything from nowhere”23Donna Haraway, “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective”, Feminist Studies, 14 (3), 1988, pp. 575–599, here: p. 581., we have conceptualised space, time and value relationally, in other words as differences in the network of mediators: Starhemberg stands on the garden terrace of Schönbrunn Palace, in front of carbon and condenser microphones; to his left an operator of Radio Wien wearing headphones and a man with a Tyrolean hat holding a still camera; among the Home Guard troops, arranged in the tree-lined avenues, a newsreel car with a movie camera on top; in the garden’s background the Gloriette; etc.24This example of a spatial distribution describes the photograph included in figure 10, which is archived in the Bildarchiv Austria. Available at: http://www.bildarchivaustria.at/Pages/ImageDetail.aspx?p_iBildID=1556436 [accessed 30 June 2018].

An experience, in the sense of our data model, is an individual subset of relations including the attached mediators. And just as in our terminology a medium is a type of mediator, a mediation is a pattern of relations (e.g. the centralised topology occurring again and again in the “Turks Deliverance Celebration”). In other words, a regularity of spatial, temporal and evaluative connections – but what is actually mediated in an experience? What drives a course of action? And how is this driving force answered in the given situation? These questions refer to the box at the foot of the data model, which summarises the Foucauldian concept of the dispositif in two words, namely as the interplay of demand and response that is at stake in every experience.25In an interview from 1977, Foucault defined the dispositif, usually translated into English as ‘apparatus’ or ‘mechanism’, as “a thoroughly heterogeneous ensemble [un ensemble résolument hétérogène]” and explicitly as “the network [le réseau] that can be established between these elements”, comprising “the said as much as the unsaid.” He emphasised, however, that he is not so much interested in categorising the connected entities, for example as discursive or material, … Continue reading While actor-network accounts focus on concrete empirical cases in order to precisely describe who or what makes a difference in a course of action, dispositif analysis searches for types of connection, for historical patterns of relations that are actualised in the given situation. Let us take the above-mentioned example of the protest against the live broadcast of the “Turks Deliverance Celebration”: the people who cancelled their registration wanted to raise their own voices and refused to be influenced or educated from above – a collective demand to which Austrian radio was not ready to respond in 1933. However, counselled by the emigrants Paul Lazarsfeld, his wife Herta Herzog and his friend Hans Zeisel, the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS) and the New York ad agency McCann-Erickson soon learned how to steer free expression of opinion in specific directions.26On the American legacy of “motivational research” (Motivforschung) conducted by former members of the Wirtschaftspsychologische Forschungsstelle in Vienna, see the (unfortunately not very precise) study by Lawrence R. Samuel, Freud on Madison Avenue. Motivation Research and Subliminal Advertising in America, Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010. I discuss this topic in a lecture on “Motive, Zielgruppen, Profile: Paul Lazarsfelds frühe Studien in Wien um 1930”, … Continue reading

Hence, the actor-network and the dispositif are the central methodological concepts that are operationalised in the data model of Campus Medius. Thus far, however, I have only elaborated on the right-hand part of the diagram in figure 13, the ontological structure of the database. To close this chapter, I will add a few words on its left-hand side, on those entities that make the stored data perceptible to the users. In order to appear on the website, a mediator needs to receive information, it literally has to be informed by texts, images, audio or video. The same applies to the mediation, which stays invisible as long as there is no link to an interface, understood here as a mapping perspective and a mode of navigation. Far from being neutral or free of ideology, these visualisations emerge from dispositifs of mediation, which are not varying representations of one reality, but rather different realities themselves.27The ontological background of this claim is explored in Bruno Latour’s research project on modern “modes of existence”, which is (more or less) situated in the field of digital humanities because it employs an online platform for a collaborative close reading. Available at: http://modesofexistence.org [accessed 30 June 2018]. Cp. Bruno Latour, An Inquiry into Modes of Existence. An Anthropology of the Moderns, translated by Catherine Porter, Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 2013 … Continue reading

IV. Mapping Modern Media

In the last chapter of the article, I will sketch out the long-term plans that we are pursuing for Campus Medius. We want to develop the website into a digital platform for mapping media experiences. Guided by a virtual assistant, the users should independently select a media experience in their daily lives, precisely describe its heterogeneous components, and map how these manifold things are connected with each other. The aim of the platform would be to subject the conceptual premises of our historical case study to a contemporary test: does having a media experience in the (post-)modern societies of the 21st century still mean using reason in sovereign signs, capturing life in examining gazes, or raising the voice in governed transmissions? In the case of the “Turks Deliverance Celebration”, these dispositifs of mediation arose from an interplay between the empirical material and a Foucauldian theory of modernity.28Foucault did not actually formulate such a theory, but in the lectures on governmentality, he summarised his studies on modernity and adjusted his approach. Instead of defining epochal shifts around 1650 and 1800, he conceptualized a sovereign, a disciplinary and a liberal regime, which can all be traced back to the 17th century but have been dominant in modern societies at various times up to the present day. Cp. Michel Foucault, Security, Territory, Population. Lectures at the Collège de … Continue reading I want to highlight the word interplay here, because no data explain themselves, but it also leads nowhere to obey a theoretical system that degrades them to mere placeholders. However, we are confident now that our data model enables us to define media and mediations immanently, so to say from below, by having hundreds of people “map modern media” and by analysing the gathered data in order to discover types of mediators and relational patterns that are distinctive of mediality as an experiential field.

The idea for this collaborative platform evolved from university courses I have taught in Europe and the United States since 2016. Instead of geo-referencing data sets, the students were encouraged to consider mapping as a critical practice by selecting and inquiring into media experiences in their daily lives: who or what is given in such a course of action? How are these mediators connected with each other? To which demand is the media experience responding? And what might an alternative response be? For these courses, I had to translate our data model into a series of practical operations or rather mapping exercises.

- Selection: What do you regard as a media experience? Choose a concrete situation, a course of action that plays a role in your everyday life, and give reasons for your choice.

- Inventory: Who or what is given in this media experience and actually makes a difference? Pick five mediators and describe the situation from each of their standpoints.

- Topology: How are the mediators connected in terms of space, time and value? Map the spatial, temporal and evaluative relations of the media experience.

- Analysis: What drives this course of action? To which urgent demand is the media experience responding? Observe, think, observe, think, finally write.

- Critique: Can you imagine another response to this demand? Which mediators are involved? How are they linked? Create a counter-map with an alternative mediation.

The exercise starts by selecting a concrete situation in everyday life that could be classified as a media experience and by explaining this choice. In the inventory, step two, the students are asked to define five mediators and describe the selected course of action from these heterogeneous standpoints. The actual mapping follows in a third step where charts or diagrams are created that visualise the relations between the mediators. I encourage the students to explore the connections in terms of space, time and value, but it is not strictly necessary for all three perspectives to be represented. Steps four and five are intended to be a critique of the analysed situation: after reflecting to which urgent demand the media experience is responding, identifying its leitmotif, an alternative response or answer should be given in the form of a counter-map.29On critique as the “art of not being governed quite so much”, cp. Michel Foucault, “What is Critique?”, translated by Lysa Hochroth [French 1978], in Michel Foucault, The Politics of Truth, edited by Sylvère Lotringer, Los Angeles, Semiotext(e), 2007, pp. 41–81, here: p. 45. On critical cartography and counter-mapping, cp. Jeremy W. Crampton and John Krygier, “An Introduction to Critical Cartography”, ACME: An International E-Journal for Critical Geographies, 4 (1), 2005, pp. … Continue reading One student of mine chose to look into her habit of watching Tatort, for example, a very popular crime series produced and aired by public service broadcasters in Germany, Austria and Switzerland. She asked herself why she views this TV drama almost every Sunday evening and concluded that she mainly appreciates the sense of community, knowing that millions of other viewers see and hear the same programme at the same time. Yet if the “sense of community” is the real motive behind this media experience, what alternatives are there to feel in touch with others? Does it have to be a community of people with a similar language and cultural background (as in the case of Tatort)? Or could it also be a collective assembling highly diverse members, both humans and non-humans?

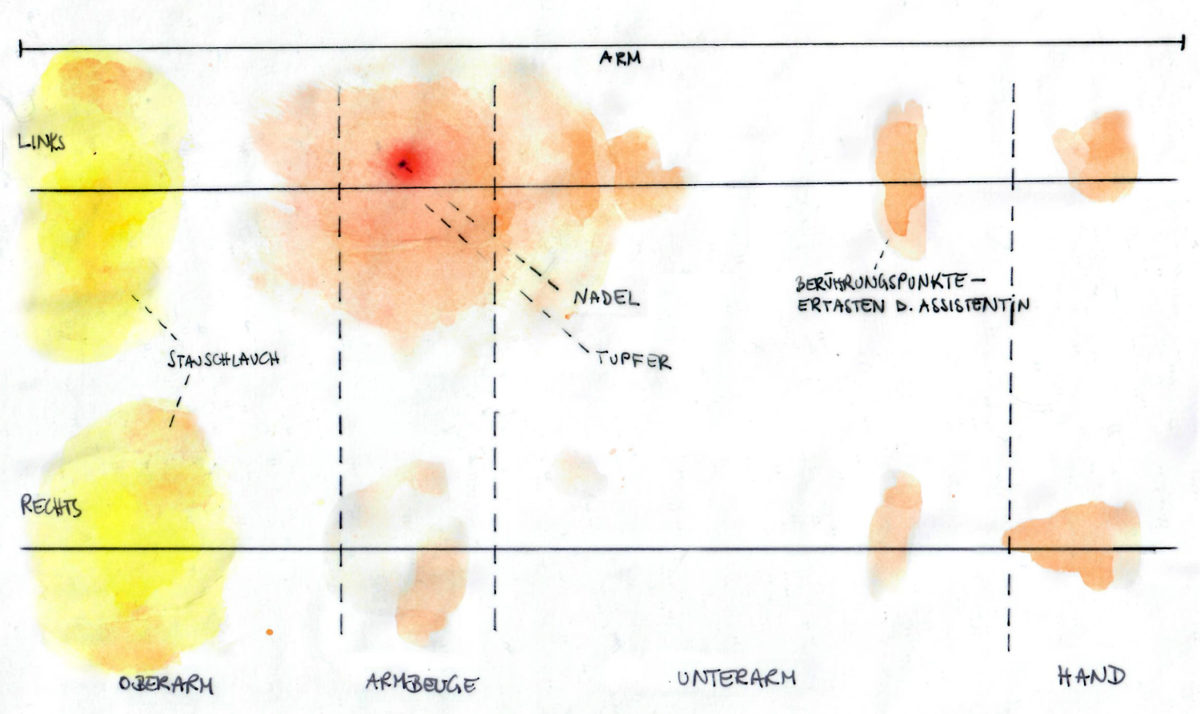

In conclusion, I will present some sketches, maps and diagrams created in my mapping courses. The first two examples were made by students from UCLA’s Center for Digital Humanities. Figure 14 shows a research map depicting the movement of the hose in a hookah session with five people sharing a water pipe, which the student described as an opportunity to have easy-going conversation. [Fig. 14] One of his classmates constructed a timeline of unboxing an iPhone, treated like a spiritual rite, and defined two points of no return, the removal of the plastic around the box and of the phone’s screen protector. [Fig. 15] The following two maps derive from a course on sound mapping at the University of Liechtenstein, where one student charted how his daily activity was influenced by pupils playing on a schoolyard nearby his office. [Fig. 16] Another participant in this class temporally arranged photos in order to visualise how he is woken every morning by a passing train. [Fig. 17] The last three drawings were created by students of media design at the University of Applied Sciences in Vorarlberg, Austria. Figure 18 outlines the intensity of concentration at the start of a paragliding flight and the following phase of relaxation in the view from above that motivated this student to spend much of her leisure time in the air. [Fig. 18] One of her classmates sketched a timeline of preparing espresso on the stove, a procedure that organises her morning routine into a phase of swift cleaning while the coffee is brewing, and a phase of calm me-time before the workday begins. [Fig. 19] The final diagram was made by a student who had a blood sample taken from a peripheral vein and documented this physical intervention in a series of sketches. [Fig. 20]

As you can see, these courses are quite experimental, a kind of laboratory to develop our digital mapping platform. The major challenge is to define a strict methodological procedure without predetermining what counts as a media experience, that is to clearly structure the steps of inquiry, but to leave the form of the inquired situation as open as possible. We aim to collaboratively map the experiential field of mediality, to explore which things are involved in media experiences and how they are related – whether the course of action be unboxing an iPhone or smoking a water pipe. In spite of this essential openness, however, the results have to be comparable so that a multitude of mappings will disclose types of mediators (i.e. media) and relational patterns (i.e. mediations).

| ↑1 | The project was supervised by Shannon Mattern, who has since published her “urban media archaeology” in two books: Deep Mapping the Media City, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 2015; Code + Clay… Data + Dirt. Five Thousand Years of Urban Media, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 2017. Most of the HTML, CSS and JavaScript programming was done by Darius Daftary. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Cp. Simon Ganahl, Karl Kraus und Peter Altenberg. Eine Typologie moderner Haltungen, Konstanz, Konstanz University Press, 2015. |

| ↑3 | Cp. Karl Kraus, Dritte Walpurgisnacht, edited by Christian Wagenknecht, Frankfurt a.M., Suhrkamp, 1989. |

| ↑4 | Cp. Mikhail M. Bakhtin, “Forms of Time and of the Chronotope in the Novel” [Russian 1975], in Mikhail M. Bakhtin, The Dialogic Imagination. Four Essays, edited by Michael Holquist, translated by Caryl Emerson and Michael Holquist, Austin, University of Texas Press, 1981, pp. 84–258. |

| ↑5 | Cp. Simon Ganahl, “Der monströse Fouleuze. Eine philosophische Lektüre von Andrej Belyjs Petersburg”, Le foucaldien, 3 (1), 2017. DOI: http://doi.org/10.16995/lefou.23. |

| ↑6 | Cp. Todd Presner, “The View from Above/Below”, in Todd Presner, David Shepard, Yoh Kawano, HyperCities. Thick Mapping in the Digital Humanities, Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 2014, pp. 84–127, here: pp. 110–118. |

| ↑7 | Cp. Bruno Latour, Reassembling the Social. An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2005. |

| ↑8 | The Digital Humanities Manifesto 2.0 (2009). Available at: http://manifesto.humanities.ucla.edu/2009/05/29/the-digital-humanities-manifesto-20 [accessed 30 June 2018]. |

| ↑9 | Cp. ANNO (Austrian Newspapers Online). Available at: http://anno.onb.ac.at [accessed 30 June 2018]. |

| ↑10 | As Foucault wrote in retrospect, his studies of modern madness, disease, criminality and sexuality explored “the historical a priori of a possible experience”. (Michel Foucault, “Foucault”, translated by Robert Hurley [French 1984], in Michel Foucault, Essential Works of Foucault. 1954–1984, vol. 2, edited by James Faubion, Harmondsworth, Penguin, 2000, pp. 459–463, here: p. 460.) |

| ↑11 | On interfaces as practices of mediation, cp. Alexander R. Galloway, The Interface Effect, Cambridge, Polity, 2012, and Johanna Drucker, Graphesis. Visual Forms of Knowledge Production, Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 2014. |

| ↑12 | Cp. Otto Neurath, International Picture Language. The First Rules of Isotype, London, Kegan Paul, 1936. |

| ↑13 | Cp. Presner 2014, pp. 84–101. |

| ↑14 | Cp. Ernst Rudiger Starhemberg, Between Hitler and Mussolini, New York/London, Harper & Brothers, 1942, pp. 95–117. |

| ↑15 | See, for example, the coverage in the semi-official newspaper Reichspost (Vienna), 15 May 1933, pp. 1–3. Available at: http://anno.onb.ac.at/cgi-content/anno?aid=rpt& datum=19330515 [accessed 30 June 2018]. |

| ↑16 | The photograph is archived in the Bildarchiv Austria. Available at: http://www.bildarchivaustria.at/Pages/ImageDetail.aspx?p_iBildID=1553954 [accessed 30 June 2018]. |

| ↑17 | Cp. “Die Türkenbefreiungsfeier des österreichischen Heimatschutzes in Wien”, Fox Tönende Wochenschau, VII/20, 15 May 1933, Filmarchiv Austria (JS 1933/8). |

| ↑18 | A short recording of the live broadcast has survived in the Österreichische Mediathek. Available at: https://www.mediathek.at/atom/136BBF40-225-02D1A-00000904-136AFAF1 [accessed 30 June 2018]. |

| ↑19 | Cp. “Die Antwort auf den Kikeriki-Sonntag”, Arbeiter-Zeitung (Vienna), 16 May 1933, p. 2. Available at: http://anno.onb.ac.at/cgi-content/anno?aid=aze&datum=193305 16&seite=2 [accessed 30 June 2018]. |

| ↑20 | Cp. Desmond Mark (ed.), Paul Lazarsfelds Wiener RAVAG-Studie 1932. Der Beginn der modernen Rundfunkforschung, Wien, Guthmann-Peterson, 1996. |

| ↑21 | Jean Bauer, “Who You Calling Untheoretical?”, Journal of Digital Humanities, 1 (1), 2011. Available at: http://journalofdigitalhumanities.org/1-1/who-you-calling-untheoretical-by-jean-bauer [accessed 30 June 2018]. |

| ↑22 | The selection of space, time and value as relational properties is based on Foucault’s analysis of power relations, especially his precise description of spatial distributions, temporal orders and evaluative rankings. Cp. Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish. The Birth of the Prison, translated by Alan Sheridan, New York, Vintage Books, 1995 [French 1975], pp. 135–228. |

| ↑23 | Donna Haraway, “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective”, Feminist Studies, 14 (3), 1988, pp. 575–599, here: p. 581. |

| ↑24 | This example of a spatial distribution describes the photograph included in figure 10, which is archived in the Bildarchiv Austria. Available at: http://www.bildarchivaustria.at/Pages/ImageDetail.aspx?p_iBildID=1556436 [accessed 30 June 2018]. |

| ↑25 | In an interview from 1977, Foucault defined the dispositif, usually translated into English as ‘apparatus’ or ‘mechanism’, as “a thoroughly heterogeneous ensemble [un ensemble résolument hétérogène]” and explicitly as “the network [le réseau] that can be established between these elements”, comprising “the said as much as the unsaid.” He emphasised, however, that he is not so much interested in categorising the connected entities, for example as discursive or material, but rather in searching for the specific “nature of the connection [la nature du lien]”. Foucault added that every dispositif “answers an urgent demand [répondre à une urgence]” by strategically fixing a social problem. (Michel Foucault, “The confession of the flesh”, translated by Colin Gordon [French 1977], in Michel Foucault, Power/Knowledge. Selected Interviews and Other Writings 1972–1977, edited by Colin Gordon, New York, Pantheon, 1980, pp. 194–228, here: pp. 194f. [trans. modified].) |

| ↑26 | On the American legacy of “motivational research” (Motivforschung) conducted by former members of the Wirtschaftspsychologische Forschungsstelle in Vienna, see the (unfortunately not very precise) study by Lawrence R. Samuel, Freud on Madison Avenue. Motivation Research and Subliminal Advertising in America, Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010. I discuss this topic in a lecture on “Motive, Zielgruppen, Profile: Paul Lazarsfelds frühe Studien in Wien um 1930”, foucaultblog, 2 July 2018. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.13095/uzh.fsw.fb.214. |

| ↑27 | The ontological background of this claim is explored in Bruno Latour’s research project on modern “modes of existence”, which is (more or less) situated in the field of digital humanities because it employs an online platform for a collaborative close reading. Available at: http://modesofexistence.org [accessed 30 June 2018]. Cp. Bruno Latour, An Inquiry into Modes of Existence. An Anthropology of the Moderns, translated by Catherine Porter, Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 2013 [French 2012], esp. chap. 6, pp. 151–178. |

| ↑28 | Foucault did not actually formulate such a theory, but in the lectures on governmentality, he summarised his studies on modernity and adjusted his approach. Instead of defining epochal shifts around 1650 and 1800, he conceptualized a sovereign, a disciplinary and a liberal regime, which can all be traced back to the 17th century but have been dominant in modern societies at various times up to the present day. Cp. Michel Foucault, Security, Territory, Population. Lectures at the Collège de France 1977–1978, translated by Graham Burchell, edited by Michel Senellart, Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan, 2007 [French 2004], esp. pp. 87–114. |

| ↑29 | On critique as the “art of not being governed quite so much”, cp. Michel Foucault, “What is Critique?”, translated by Lysa Hochroth [French 1978], in Michel Foucault, The Politics of Truth, edited by Sylvère Lotringer, Los Angeles, Semiotext(e), 2007, pp. 41–81, here: p. 45. On critical cartography and counter-mapping, cp. Jeremy W. Crampton and John Krygier, “An Introduction to Critical Cartography”, ACME: An International E-Journal for Critical Geographies, 4 (1), 2005, pp. 11–33, and the inspiring “critical cartography primer” in Annette Miae Kim, Sidewalk City. Remapping Public Space in Ho Chi Minh City, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2015, pp. 112–145. |

Simon Ganahl is habilitation fellow (APART) of the Austrian Academy of Sciences and lecturer at the Universities of Vienna, Zurich, Liechtenstein and Vorarlberg. Studies of communication and German philology in Vienna, Hamburg and Zurich (PhDs in both fields). 2012–13 visiting researcher in the School of Media Studies at The New School in New York; 2016 visiting lecturer in the Center for Digital Humanities at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). Co-founder and co-editor of the peer-reviewed open access journal Le foucaldien (foucaldien.net); principal investigator of the digital mapping project Campus Medius (campusmedius.net). Latest book: Karl Kraus und Peter Altenberg: Eine Typologie moderner Haltungen (Konstanz University Press 2015).