Disobedient Sensing and Border Struggles at the Maritime Frontier of EUrope

The Maritime Frontier’s Conflictual Aesthetic Regime

In 2015, the phenomenon of migrants seeking to contest their legal exclusion from the territory of EUrope by crossing the sea, reached unprecedented dimensions. More than one million people crossed the Mediterranean Sea, while more than 3.700 people died in the attempt.1Our paper employs the term ‘EUrope’ throughout. In this way it seeks to problematise frequently employed usages that equate the EU with Europe and Europe with the EU and suggests, at the same time, that EUrope is not reducible to the institutions of the EU. A year later, also due to novel and reinforced EUropean deterrence measures, crossings via the Aegean Sea dropped dramatically but increased via the Central Mediterranean Sea. By the end of 2016, more than 360.000 people had survived the journey. The official death toll, however, stood at 5.096 – a new harrowing record.2Cp. UNHCR, “Mediterranean: Dead and Missing at Sea. January 2015 – 31 Decemeber 2016”, UNHCR. The UN Refugee Agency, 2017. Available at: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/download/53632 [accessed February 24, 2017]. Over the past two decades, and in particular over the past few years, one has become accustomed to the images of overcrowded vessels and shipwrecked travellers which circulate nearly daily through the international media landscape. Only rarely do we learn about individual fates, such as the Syrian toddler Alan Kurdi, whose body washed ashore in Turkey. His image received global attention, symbolising the desperation of displaced people but did not, however, necessarily prompt a critical conversation on the economies of violence underlying contemporary border regimes, or on the political dimension of migrants’ movements across borders.3Cp. Kim Rygiel, “Dying to live: migrant deaths and citizenship politics along European borders: transgressions, disruptions, and mobilizations”, Citizenship Studies, 20(5), 2016, pp. 545–560.

Illegalised migration across the Mediterranean Sea and its control is predominantly perceived through media images of indistinguishable masses of non-white bodies crammed onto unseaworthy vessels, images which are routinely embedded in a rhetoric of invasion and alarm in the face of the ‘Mediterranean migration crisis’.4Cp. New Keywords Collective, “Europe/Crisis: New Keywords of ‘the Crisis’ in and of ‘Europe’”, in Nicholas De Genova and Martina Tazzioli (eds.), Near Futures Online, 2016. Available at: http://nearfuturesonline.org/europecrisis-new-keywords-of-crisis-in-and-of-europe/ [accessed January 1, 2017]. These images operate within an ambivalent regime of (in)visibility at play at EUrope’s maritime frontier, a “partition of the sensible” in the terms of Jacques Rancière, which occludes as much as it reveals: It creates particular conditions of (dis)appearance, (in)audibility, (in)visibility.5Cp. Nicolas De Genova, “Spectacles of migrant ‘illegality’: the scene of exclusion, the obscene of inclusion”, Ethnic and Racial Studies, 36(7), 2013, pp. 1190–1198. Jacques Rancière, The Politics of Aesthetics, London, Continuum, 2006. As a result of migrants’ illegalisation, they seek to cross borders undetected, clandestinely in the etymological connotations and secrecy of this word. As opposed to the logic of clandestinity, what all agencies aiming to control migration try to do, is to shed light on migration and in particular on acts of unauthorised border crossings in order to make the phenomenon of migration more knowable, predictable and governable. To this effect, a vast dispositif of control has been deployed at the maritime frontier of EUrope, one made of mobile patrol boats but also of and an assemblage of surveillance technologies, through which border agents seek to detect and intercept migrants’ vessels.6Cp. Lorenzo Pezzani and Charles Heller, “Liquid Traces: Investigating the Deaths of Migrants at the Maritime Frontier of the EU”, in Forensic Architecture (ed.), Forensis: The Architecture of Public Truth, Berlin, Sternberg Press, 2014.

However, the partition of the sensible at EUrope’s maritime borders is more ambivalent than this binary opposition would let us believe. Migrants in distress may do everything they can to be seen, so as to be rescued, and conversely border agents may seek not to see migrants in certain instances, as we documented in the left-to-die boat case described below, considering that rescuing them at sea would entail responsibility for disembarking them and processing their asylum claims and/or deporting them. This points to the fact that the light shed on the maritime frontier by agents of border control is highly selective. Through the constant circulation of images of overcrowded boats, the “border spectacle” so incisively analysed by Nicholas de Genova, simultaneously spectacularises the transgression of the border and the neutralisation of the “threat” of migration by state actors, and keeps the state production of illegality through policies of exclusion, the structural violations of migrant rights at the border, and their future exploitation in EUropean economies, in the dark.7Nicholas De Genova, “Spectacles of migrant ‘illegality’”, p. 1183.

Through selective spectacularisations, migrant death at sea is routinely folded into naturalising and depoliticising narratives, within which the fate of precarious travellers seems to depend on their struggle with the natural forces at work in the Mediterranean – the winds, the currents, the waves, and the cold.8Cp. Maurice Stierl, “A Sea of Struggle – Activist Border Interventions in the Mediterranean Sea”, Citizenship Studies, 20(5), 2016, pp. 561–578. Serving as EUrope’s alibi, the loss of thousands of lives can be conveniently blamed on the forces of the sea or on third parties, especially human smugglers. Within these narratives, critique of EUrope and its border authorities would revolve solely around a supposed passivity, a lack of engagement, and often give rise to calls for increased intervention, more militarisation, and for reinforced and externalised border control measures to pre-emptively halt migration movements before reaching the space of the sea in the first place. In these hegemonic narratives, EUrope’s border activities, always already at work to significantly shape this borderzone and to condition migrant experiences, become effaced and invisibilised.

While the deaths of migrants at sea have long appeared as an obscene supplement of the border spectacle, recently a partial reversal has occurred within what William Walters has called the “humanitarian border” – a way of governing migration that seeks to compensate for the social violence embodied in the regime of migration control.9William Walters, “Foucault and frontiers: notes on the birth of the humanitarian border”, in: Ulrich Bröckling, Susanne Krasmann and Thomas Lemke (eds.), Governmentality: Current Issues and Future Challenges, New York, Routledge, 2011, pp. 138–164. While rescue at sea by rescue agencies have long been the clear humanitarian counterpart of the illegalisation of migrants which forces them to resort to clandestine means of crossing in the first place, the deaths of migrants have come to be increasingly spectacularised, however only to denounce the practices of smugglers. As a result, the violence of borders still remains hidden, not only because the denunciation of smugglers serves to divert attention from it, but because border control becomes framed as an act of saving migrants and its violence is covered up by a humanitarian varnish. The aesthetic regime imposed by the EUropean border regime on the Mediterranean is thus a complex and conflictual field, where visibility and invisibility do not designate two discrete and autonomous realms, but rather a topological continuum, within which any practice that seeks to contest the deadly border regime must position itself carefully.

A Disobedient Gaze: Turning Surveillance Against Itself

For several years now, transborder activists struggling against the EUropean border regime have sought to contest this regime of selective (in)visibility. Migrant and refugee rights organisations have long protested the mass dying at sea, and denounced it as a consequence of EUrope’s policies of deterrence, exclusion, and border militarisation.10See in particular the database established by UNITED and the maps produced by Migreurop based upon them. They were, however, hardly able to document events within the maritime frontier to demand accountability for these deaths, and even less able to actually intervene in real-time into ongoing struggles at sea to avert them and enable the crossing of borders. Recently, researchers and activists have developed new practices that have enabled them to claim and enact the right to look and the right to listen in the unlikely and seemingly inaccessible spaces of the sea. In that way, they also began to challenge the borders of what could be seen and heard.

An initial intervention and a significant breach in the simultaneous spectacularisation and invisibilisation of the maritime frontier, came through the Forensic Oceanography project. Uncovering the case of the so-called “left-to-die boat” in 2011, the project’s first report offered an account and analysis of a particularly harrowing maritime tragedy.11For our reconstruction of these events, see our report: Charles Heller, Lorenzo Pezzani, and Situ Studio, “Forensic Oceanography. Report on the ‘Left-To-Die Boat’”, Forensic Architecture, 2011. Available at: www.forensic-architecture.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/FO-report.pdf [accessed June 10, 2017]. Our video animation Liquid Traces summarises our findings. At the height of the NATO-led military intervention in Libya, 72 travellers fleeing Libya were left to drift in the Central Mediterranean Sea for 15 days, despite distress signals sent out to all vessels navigating in this area, and despite several encounters with military aircrafts and a warship. While the testimonies of the nine survivors brought this crime of failing to render assistance that cost the lives of 63 people to light, its perpetrators remained, at first, unidentified.

In conjunction with a coalition of NGOs, and in collaboration with several parallel investigations, Charles Heller and Lorenzo Pezzani reconstructed a composite image of the events by corroborating the survivors’ testimonies with information provided by the vast apparatus of remote sensing technologies that have transformed the contemporary ocean into a digital archive of sorts: optical and thermal cameras, radars, vessel tracking technologies, distress signals which contained geo-referenced coordinates, wind and current data, satellite imagery, and so forth. By interrogating this sensorium, we were able to model and reconstruct the drifting boat’s trajectory as well as to account for the presence of a large number of vessels in the vicinity of the drifting migrant boat that did not heed their calls for help. While these technologies are often used for the purpose of policing illegalised migration as well as the detection of other ‘threats’, they were repurposed to find evidence for the failure to render assistance. The reconstruction of events formed the basis of several ongoing legal cases against states whose assets were in operation at the time of the events.12Cp. fidh, “63 migrants morts en Méditerranée: des survivants poursuivent leur quête de justice”, fidh, June 18, 2013. Available at: https://www.fidh.org/La-Federation-internationale-des-ligues-des-droits-de-l-homme/droits-des-migrants/63-migrants-morts-en-mediterranee-des-survivants-poursuivent-leur-13483 [accessed June 10, 2017]. Through our work on the ‘left-to-die’ case, we sought to put into practice a disobedient gaze that used some of the same sensing technologies of border controllers, but sought to redirect their ‘spotlight’ from unauthorised acts of border-crossing, to state and non-state practices violating migrants’ rights. We conceived this gaze as

“[aiming] not to disclose what the regime of migration management attempts to unveil – clandestine migration – but unveil that which it attempts to hide, the political violence it is founded on and the human rights violations that are its structural outcome.”13Lorenzo Pezzani, and Charles Heller, “A disobedient gaze: strategic interventions in the knowledge(s) of maritime borders”, Postcolonial Studies, 16(3), 2013, pp. 289–298, here: p. 294 (emphasis in original).

Through our critical observations and counter-mapping practices of the sea, we demonstrated how a variety of actors and technologies interact to shape this space, and how EUrope actively employs the sea and its forces for the purpose of migrant deterrence. Far from being an empty expanse where migrant tragedies occur seemingly ‘naturally’, the sea forms a deeply political space, where struggles over human movement and its policing are continuously being played out. While facing systematic forms of oppression that significantly condition irregularised attempts to traverse the Mediterranean, the subjects of sea crossings are protagonists of these struggles who enact their right to leave, move, survive and arrive. Hence, it is crucial to understand the ‘viapolitics’ of Mediterranean migration, where the migrant boat is, in fact, “a site of political action”, as Walters has argued.14William Walters, “Migration, vehicles, and politics: Three theses on viapolitics”, European Journal of Social Theory, 18(4), 2015, pp. 469–488, here: p. 481.

Through WatchTheMed, founded in 2012 in collaboration with a wide network of NGOs, activists, and researchers, we sought to collectivise and multiply this practice of disobedient observation as political intervention. In another detailed investigation, we contributed to uncover events that transpired in the Central Mediterranean Sea on the 11th of October 2013, leading to the loss of more than 260 lives.15Cp. Watch the Med, “Over 200 die after shooting by Libyan vessel and delay in rescue”, Watch the Med, 2013. Available at: http://watchthemed.net/reports/view/32 [accessed January 8, 2017]. By remapping the trajectory of the migrant boat that had fled from Libya, and by reconstructing distress calls, as well as the responses of responsible authorities, or rather the lack thereof, we showed how the many fatalities could have been prevented. However, as a result of Italy and Malta’s reluctance to carry out search and rescue operations, time was lost and rescue measures were delayed. When the rescue forces finally arrived at the scene, about half of the travellers had already drowned. Only years later, in May 2017, this case received wide public attention, following the release of an audio recording on which the pleas of passenger Dr Jammo to the Italian coastguards and the latter’s reluctance to help can be heard.16Cp. Samuel Osborne, “Horrific phone calls reveal how Italian Coast Guard let dozens of refugees drown”, Independent, May 8, 2017. Available at: http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/italian-navy-lets-refugees-drown-migrants-crisis-asylum-seekers-mediterranean-sea-a7724156.html [accessed June 10, 2017].

Disobedient Listening: Amplifying Migrants’ Mobile Commons

In light of this case and the ongoing mass suffering at sea, the need to find ways to intervene directly within maritime borders became ever more pressing.17Cp. Watch the Med, “Guardia Civil runs over refugee boat near Lanzarote”, Watch the Med, 2012. Available at: http://watchthemed.net/index.php/reports/view/33 [accessed May 23, 2015]. Through the WatchTheMed monitoring platform, our hope was, on the one hand, to be able to multiply the documentation of violations, and, on the other, to move towards real-time interventions so as to shift from a post-fact analysis to actually preventing violations and deaths from occurring in the first place. The WatchTheMed platform, which was initially used as a tool in the service of the tradition of documenting, denouncing, and seeking accountability for violations, as exemplified by the work of the GISTI and Migreurop networks, was seized by another important militant tradition that explicitly referred to the abolitionist network of secret routes and safe houses used by escaping enslaved populations in the US: the ‘underground railroad’.18For a discussion of the connection with the underground railway of anti-slavery within migrants’ rights activists discourse, see: Welcome to Europe Network, “From Abolitionism to Freedom of Movement? History and Visions of Antiracist Struggles”, Noborder lasts forever, Frankfurt am Main, 2010. Available at: http://conference.w2eu.net/files/2010/11/abolitionism.pdf [accessed June 10, 2017]. Regarding themselves as part of an existing transnational underground railroad that supports trans-border mobilities and migratory acts of escape, activist networks such as NoBorder and Welcome to Europe, have long directly supported unauthorised mobilities across EUropean borders. Migration is understood by these networks as a social movement in its own right, as a “creative force” that upsets the government of mobility imposed by the border regime not only by means of “explicit” legal and political claims (such as those grounded on the documentation and denunciation of specific episodes of violence at the border) but also through an everyday practice of refusing the border. This perspective opens up the field of struggles for freedom of movement to a whole series of “imperceptible” practices that would otherwise not be included in the political field, modifying the very borders of what we understand as political.19Dimitris Papadopoulos, Niamh Stephenson, and Vassilis Tsianos, Escape Routes: Control and Subversion in the 21st Century, London, Pluto Press, 2008. Brett Neilson and Angela Mitropoulos have tellingly made this point in a passage that is worth quoting at length:

“In the case of struggles surrounding undocumented migration, the very notion of movement fractures along a biopolitical or racialised axis: between movement understood in a political register (as political actors and/or forces more or less representable) and movement undertaken in a kinetic sense (as a passage between points on the globe or from one point to an unknown or unreachable destination). To keep these two senses of movement separate not only denies political meaning to the passages of migration but, also, fails to think through the complexities of political movement as such, not simply as the incompleteness and risk of every politics but, more crucially, as the necessarily kinetic aspects of political movements that might be something more, or indeed other, than representational. […] It is in this nexus of ‘movement as politics’ and ‘movement as motion’ that the non-governmental struggles over undocumented migration take shape as challenges to the demarcations that define politics as always, inexorably, national and/or sovereign.”20Angela Mitropoulos and Brett Neilson, “Exceptional Times, Non-Governmental Spacings, and Impolitical Movements”, Vacarme, January 8, 2006. Available at: http://www.vacarme.org/article484.html [accessed June 10, 2017].

It is this reframing of the political meaning of ‘movement’ that grounds activist practices seeking to facilitate and sustain migrants’ unauthorised movements. Acknowledging that unauthorised migration in our bordered world are often enabled by ‘under the surface’ knowledge economies and networks composed of the very subjects of migration, their friends, relatives and connected communities and allies, activist networks sought to practice solidarity by creating further ‘pillars’ of the underground railroad. One such example is the creation of an online guide for migrants and refugees that provides practical information for their journeys towards and within EUrope.

Inspired by this tradition, the WatchTheMed network also started to produce a series of leaflets containing information about the risks, rights, and safety measures at sea.21Cp. Watch the Med, “Safety at Sea. Instructions for a Distress Call”, Watch the Med. Available at: http://watchthemed.net/index.php/page/index/10 [accessed May 23, 2015]. All these political interventions sought to contribute to already existing ‘knowledges of circulation’ which emerge from the collective experience of transnational irregularised migration. As Mehdi Alioua and Charles Heller write, the social network that is progressively constituted through the experience of migration “is what allows [migrants] to make the link between the stages, obtaining information about the spaces they intend to traverse and the ways to enter into contact with the collectives there who might be of help to them. Knowing how to cross borders is a know-how that is built up gradually and tried out collectively at the different stages of the trip.”22Medhi Alioua and Charles Heller, “Transnational Migration, Clandestinity and Globalization: The Case of Sub- Saharan Transmigrants in Morocco”, in: Gerlinde Vogl, Susanne Witzgall, and Sven Kesselring (eds.), New Mobilities Regimes in Art and Social Sciences, Farnham, Ashgate, 2013, pp. 175–84. In this sense, the mobility of migrants constitutes an infrastructure of sorts, one that includes not only the footpaths, highways, train lines, or airports through which precarious travellers move; not only the wireless networks that transmit their information, the internet café where they chat with relatives and friends, the mobile phones with which they alert the coastguards and the satellite phone which locates their GPS position; it includes what has also been referred to as ‘mobile commons’, i.e. “a world of knowledge, of information, of tricks for survival, of mutual care, of social relations, of services exchange, of solidarity and sociability that can be shared, used and where people contribute to sustain and expand it.”23Dimitris Papadopoulos and Vassilis S. Tsianos, “After Citizenship: Autonomy of Migration, Organisational Ontology and Mobile Commons”, Citizenship Studies, 17(2), 2013, pp. 178–196, here: p. 190; see also Ilker Ataç, Kim Rygiel, and Maurice Stierl, “The Contentious Politics of Refugee and Migrant Protest and Solidarity Movements: Remaking Citizenship from the Margins”, Citizenship Studies, 20(5), 2016, pp. 527–544.

The creation of the Alarm Phone, an activist hotline supporting boats in distress in the Mediterranean Sea, was the next crucial step in the collectivisation of these activist and militant practices, a new nodal point and pillar in the transnational underground railroad.24Cp. Alarm Phone, Official Website. Available at: http://alarmphone.org/ [accessed June 10, 2017]. Initiated by a coalition of freedom of movement, human rights, and migrant activist groups, including WatchTheMed, Boats4People, Welcome to Europe, Afrique Europe Interact, Borderline-Europe, No Borders Morocco, FFM and Voix des Migrants, the Alarm Phone was launched in October 2014, with the intention to respond to violent border ‘protection’ practices and the unabated mass dying in maritime spaces around EUrope, and to offer travellers alternative ways to make their distress heard.

Thanks to a management software, the Alarm Phone can re-route distress calls to a vast number of volunteers operating shifts, situated in about 12 countries, thus ensuring that every call is attended to. Due to the very different conditions in the maritime spaces of the Mediterranean, specific handbooks with step-by-step emergency plans and instructions had to be written, based on years of experience in migration and Noborder struggles as well as local and region-specific expertise. In addition to meteorological and geographical conditions, the organisation and modes of irregularised travelling differ considerably in the Mediterranean Sea. The build and size of vessels vary, many have (often malfunctioning) engines, some carry only paddles. Precarious travellers in the Aegean Sea often carry smartphones, which makes tracing them significantly easier than finding the whereabouts of those leaving from Moroccan shores, who usually only carry regular mobile phones. But, at least, they often have mobile phone reception, not available to the same extent in the Central Mediterranean Sea. Then again, groups leaving from Libya often keep a satellite phone on their vessel which allows most of them to quickly pass on GPS coordinates and which can even be charged with credit, often by the activists, from afar.

In its two years of existence, the phone project has gathered extraordinary momentum, supported about 1.800 boats in distress, and has thus proven to be one of the most important political interventions against EUrope’s border regime in recent years. Besides supporting precarious human mobilities at sea, the wide solidarity network of the Alarm Phone, composed of about 150 activists and several connected organisations, can exercise pressure when there is a risk that a violation at sea may be perpetrated, such as cases of failing to render assistance or push-back, the illegal collective expulsion of ‘aliens’ from a country’s territory, or even direct assaults on migrant groups, such as those perpetrated by units of the Greek coastguards in the Aegean Sea. Among dozens of such cases that were uncovered by the Alarm Phone was a push-back operation carried out by the Greek authorities in cooperation with the Turkish coastguards and in the presence of the EUropean border agency Frontex on the 11th of June 2016. Fifty-three people had already crossed the territorial line and entered Greek waters where they were illegally transferred, at gunpoint, onto a Turkish coastguard vessel and returned to Turkey.25Cp. WatchTheMed, “WatchTheMed Alarm Phone denounces illegal push-back operation with Frontex present”, Watch the Med. Alarmphone, 2016. Available at: https://alarmphone.org/en/2016/06/15/watchthemed-alarm-phone-denounces-illegal-push-back-operation-with-frontex-present/?post_type_release_type=post [accessed January 8, 2017]; see also: Maurice Stierl, “Every refugee boat a rebellion? Supporting border transgressions at sea”, Open Democracy, September 18, 2016. Available at: … Continue reading

Through its ability to directly follow trajectories of migrant boats in real-time, and to document and scandalise violations at sea based on information and data passed on by precarious passengers themselves, the Alarm Phone has significantly altered the ways in which in/visibility is being played out at sea and tapped into ‘migrant digitalities’, facilitating disobedient forms of irregularised migration, where migration can be conceived “as a multidirectional, dynamic movement, that is, a networked building system facilitated to a great extent by information and communication technologies”26Andoni Alonso, and Pedro J. Oiarzabal, Diasporas in the New Media Age, Reno, University of Nevada Press, 2010, p. 5.. Several of the hotline’s members have experienced sea crossings themselves and now support the project by, for example, sharing their embodied expertise and offering linguistic capabilities fundamental to adjust to the many languages spoken on board, ranging from French, Arabic, Urdu, and Farsi to English, Tigrinya, and others.

Crucial in the intervention of the Alarm Phone is thus not so much high-tech remote sensing devices such as satellite imagery that were central to report on the ‘left-to-die’ boat, but simple mobile and satellite phones and the interpersonal networks they connect. Furthermore, these mobile connections operate less through the sense of sight than the sense of sound. While it may seem paradoxical, the best instruments for the exercise of a critical right to look and observe in maritime borderzones are those that transfer sounds. This is consistent with many instruments required for oceanography, such as sonars that use sound waves to ‘see’ in the water and measure the sea’s depth instead of technologies relying on light which does not travel far beneath the ocean’s surface. Listening to those in the process of crossing maritime spaces then allows to disobediently observe the Mediterranean Sea. By employing the word sensing, we point precisely to how the entanglement of these different practices blurs the distinctions between rigid notions of “the senses”.

Mobile lines of communication have long been a crucial means of connection amongst migrant and diaspora communities. Especially for precarious and illegalised travellers, mobile phones function as orientation devices and become, as Maurice Stierl has shown, “carriers of life signals and signs of survival”27Maurice Stierl, “A Sea of Struggle”, p. 561.. Several ‘private alarm hotlines’ established by relatives and friends of people on the move as well as by activists, have played a crucial role in countless cases of distress, including the ‘left-to-die’ boat case cited above, during which the initial information of distress was relayed by satellite phone to Father Mussi Zerai, an Eritrean priest who has become a point of reference for the East African diaspora. The Alarm Phone has been able to tap into these networks, operating under the surface and beyond the gaze of sovereign control. Vital information for crossing borders and unauthorised journeys circulate in real-time and allow for direct exchange, intervention, and assistance. Smart phones in particular function as a medium of immediate information transfer: snapshots of GPS locations can be forwarded via WhatsApp or Viber, distress situations are made public via Facebook, and border guard violence can be filmed, circulated, and denounced. In the activities of the Alarm Phone, the two activist traditions we have outlined above, one based on documentation/denunciation and the other based on assisting migrants’ while on their journey, find perhaps a new convergence, insofar as acts of documentation and denunciation of violence at the border are understood as tools that enable migrants’ movements rather than simply as claims for greater compliance with human rights standards.

The mode of intervention of the Alarm Phone however was predicated on the presence of (state) vessels at sea that could be called upon and pressured to intervene to rescue migrants in distress. This is precisely what was challenged by the termination of the Italian Mare Nostrum operation, a large-scale military and humanitarian operation deployed in October 2014 off the coast of Libya. With the end of the operation, which had come under attack for constituting a “pull-factor”, we witnessed in early 2015 the creation of a lethal search and rescue gap.28We have detailed this policy shift and its effects in our report deathbyrescue.org. This resulted in the deployment of a record number of nongovernmental humanitarian rescue boats by large organisations such as Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) and several much smaller initiatives. By contributing to rescuing several tens of thousands of lives since 2015, this fleet of “Mediterranean border humanitarians” has further widened the breach in the state-imposed regime of (in)visibility at sea.29Maurice Stierl, “A Fleet of Mediterranean Border Humanitarians”, Antipode, 2017. Available at: doi: 10.1111/anti.12320 [accessed June 10, 2017].

Contesting the boundaries of the (in)visible and (in)audible has thus been a crucial aspect in the contestation of border violence.

The Subjects and Practices of Politics in the Interstitial Space of the Sea

Together, the movements of illegalised migrants across EUrope’s maritime frontier through which they contest the contemporary geography of banishment, the use of innovative technologies and methodologies to break the impunity for deaths and violations at sea, the creation of an Alarm Phone network to force actors at sea to carry out rescues, and the deployment of a humanitarian fleet to contest and partly make up for the retreat of state-led search and rescue operations, have all transformed the interstitial space of the Mediterranean into a fundamental arena of politics. Through these combined practices, illegalised migrants and those who support them seek to contest the government of migration across the sea. While we have described these distinct yet interconnected practices above, how should we conceptualise them together as distinct forms of political practice? To begin to answer this question, we must inscribe them within the particular political space in which they operate, the sea.

The distinct characteristics of the political geography of the sea are well captured by the following comment by Commander Borg of the Armed Forces of Malta: “When you have a land border, here is country A and therefore the subject of law is country A, and here is country B, there is no limbo in between. At sea it’s different. Here you have country A, here you have the high seas and here begins the jurisdiction of country B. But in between, on the high seas, things are a little bit delicate.”30Quoted in Silja Klepp, “A Contested Asylum System: The European Union between Refugee Protection and Border Control in the Mediterranean Sea”, European Journal of Migration and Law, 12, 2010, pp. 1–21. As the very name of the “Mediterranean” indicates, the sea is an interstitial space lying between territorial polities which divide the lands of our planet. While architects and scholars located in border studies and political geographies have, for several years, contested the spatial imaginary of the border as a line without thickness, the extended border zone of the sea challenges this imaginary particularly forcefully.31See for example Eyal Weizman, Hollow Land: Israel’s Architecture of Occupation, London, Verso, 2007.

The world’s oceans constitute a vast and deep frontier zone, which both separates and connects not a handful of states as on land, but all coastal states.32Cp. Paolo Cuttitta, “Le monde-frontière. Le contrôle de l’immigration dans l’espace globalise”, Cultures & Conflits, 68, 2007, pp. 61–84. In this sense, it is a topological border, which establishes a relational proximity between distant territories that are put into contact by maritime circulation – you may cross the line of the border in the port of Dakar and cross it again in Marseille. While no state can exercise exclusive sovereignty over the frontier zone of the sea, all states exercise partial rights and obligations which often overlap and conflict with each other. At work then is a form of “unbundled” sovereignty described by Saskia Sassen, in which the rights and obligations that compose modern state sovereignty on the land are decoupled from each other and applied to varying degrees depending on the spatial extent and the specific issue in question.33Cp. Saskia Sassen, Territory, Authority, Rights: From Medieval to Global Assemblages, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2006. See also Philip E. Steinberg, “Lines of Division, Lines of Connection: Stewardship in the World Ocean”, Geographical Review, 89(2), 1999, pp. 254–264 and Philip E. Steinberg, “Free sea”, in: Stephen Legg (ed.), Spatiality, Sovereignty and Carl Schmitt: Geographies of the Nomos, London, Routledge, 2011, pp. 268–275.

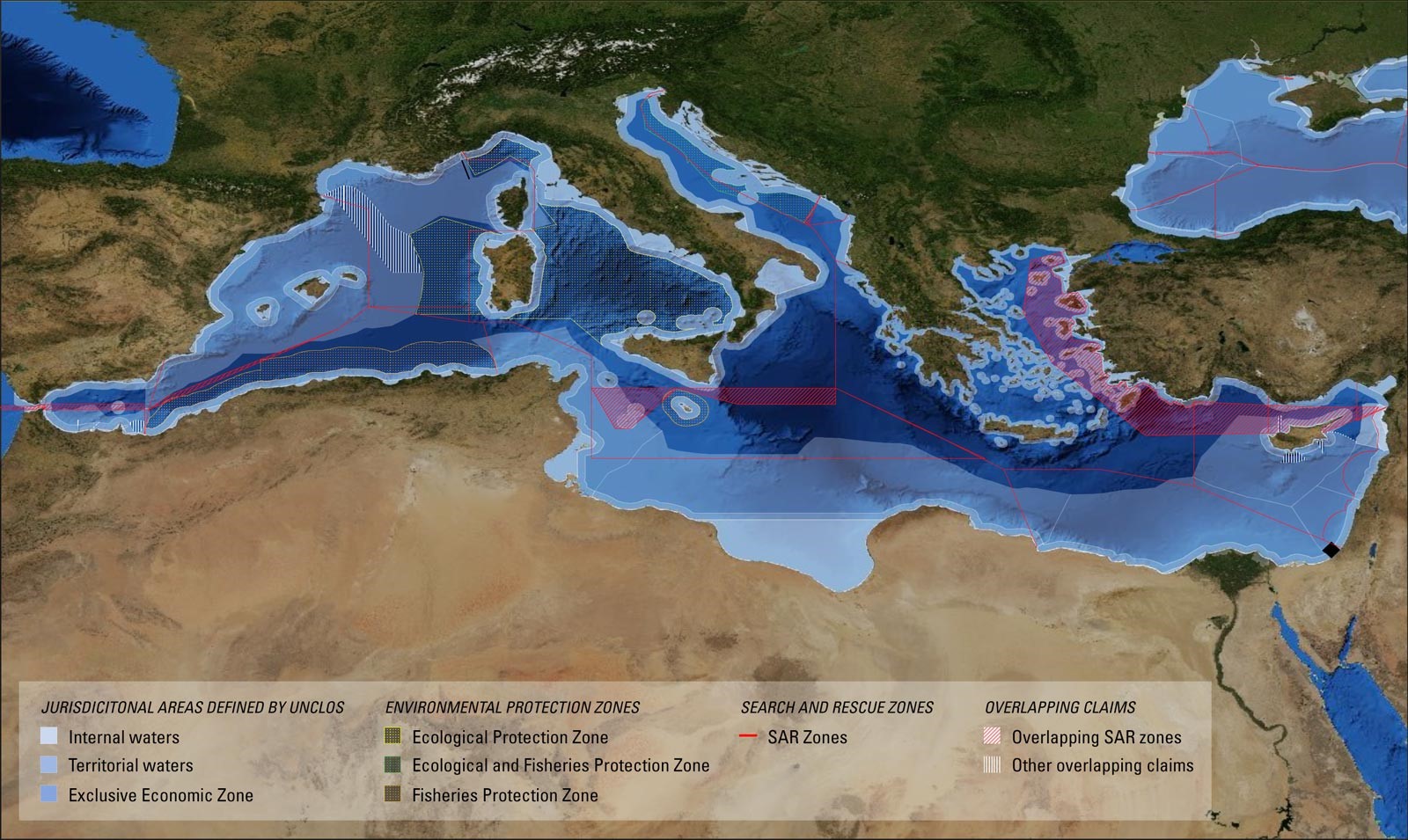

As a result, the moment of border crossing at sea is expanded into a process that can last several days and extends across an uneven and heterogeneous territory “in which the gaps and discrepancies between legal borders become uncertain and contested”34Brett Neilson, “Between Governance and Sovereignty: Remaking the Borderscape to Australia’s North”, Local-Global Journal, 8, 2010: pp. 124–140, here: p. 126. Available at: http://mams.rmit.edu.au/56k3qh2kfcx1.pdf [accessed June 10, 2017].. As soon as a migrant boat starts navigating, it passes through the various jurisdictional regimes that crisscross the Mediterranean: from the various areas defined in the UN Convention on the Laws of the Sea to Search and Rescue regions, from ecological and archaeological protection zones to areas of maritime surveillance (see the figure below). At the same time, it is caught between a multiplicity of legal regimes that depend on the juridical status applied to those onboard (refugees, economic migrants, illegals, etc.), on the rationale of the operations that involve them (rescue, interception, etc.) and on many other factors. These overlaps, conflicts of delimitation, and differing interpretations are not malfunctions but rather a structural characteristic of the maritime frontier that has allowed states to simultaneously extend their sovereign privileges through forms of mobile government and elude the responsibilities that come with it – as in the case of the left-to-die boat.35Cp. Philip E. Steinberg, The Social Construction of the Ocean, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2001; Thomas Gammeltoft-Hansen and Tanja E. Alberts, “Sovereignty at Sea: The Law and Politics of Saving Lives in the Mare Liberum”, DIIS Working Paper 18, 2010; Juan Luis Suárez de Vivero, Jurisdictional Waters in the Mediterranean and Black Seas, Bruxelles, European Parliament, 2010.

Design: Forensic Oceanography

In a sense, then, we could argue that while the current form of the territorial state on firm land is founded on an imaginary of sedentariness, the political form of maritime space is founded on movement and its management – the policing of the so-called “freedom of the seas”. The particular political geography of the sea and the type of government that is exercised across it have in turn resulted in the aforementioned political practices to contest it. What is distinctive about them, is that they strictly concern the government of movement across borders – in this case the extended frontier zone of the sea. Illegalised migrants seize a right to move across borders which is denied to them, and contest through this very act, the dictatorial nature of all migration policies. As Étienne Balibar has underlined, migrants are by definition excluded from the institutional political process that shapes national migration policies.36Étienne Balibar, We, the People of Europe? Reflections on Transnational Citizenship, Princeton, University Press, 2004, p. 109. Since the government of mobility across the sea is not imposed by one state but by many, at times operating in alliance, as in the current European operations of Frontex or EUNAVFOR MED, but also conflicting with each other, as in the conflict over search and rescue between Italy and Malta, the support to illegalised migrants draws citizens of multiple nationalities to deploy their senses and bodies to this frontier zone.

In this sense, the space of the sea has bread novel forms of political practices that mirror the form of power exercised across it: transnational nongovernmental practices which take the government of mobility as their main target. Performed in the interstices of territorialised polities, these combined practices seize the right to move, contest and transform the way the movement of people is governed. Through them, the sea is recognised as a political space in its own right, and movement is recognised as a fundamental dimension of our life in common.

| ↑1 | Our paper employs the term ‘EUrope’ throughout. In this way it seeks to problematise frequently employed usages that equate the EU with Europe and Europe with the EU and suggests, at the same time, that EUrope is not reducible to the institutions of the EU. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Cp. UNHCR, “Mediterranean: Dead and Missing at Sea. January 2015 – 31 Decemeber 2016”, UNHCR. The UN Refugee Agency, 2017. Available at: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/download/53632 [accessed February 24, 2017]. |

| ↑3 | Cp. Kim Rygiel, “Dying to live: migrant deaths and citizenship politics along European borders: transgressions, disruptions, and mobilizations”, Citizenship Studies, 20(5), 2016, pp. 545–560. |

| ↑4 | Cp. New Keywords Collective, “Europe/Crisis: New Keywords of ‘the Crisis’ in and of ‘Europe’”, in Nicholas De Genova and Martina Tazzioli (eds.), Near Futures Online, 2016. Available at: http://nearfuturesonline.org/europecrisis-new-keywords-of-crisis-in-and-of-europe/ [accessed January 1, 2017]. |

| ↑5 | Cp. Nicolas De Genova, “Spectacles of migrant ‘illegality’: the scene of exclusion, the obscene of inclusion”, Ethnic and Racial Studies, 36(7), 2013, pp. 1190–1198. Jacques Rancière, The Politics of Aesthetics, London, Continuum, 2006. |

| ↑6 | Cp. Lorenzo Pezzani and Charles Heller, “Liquid Traces: Investigating the Deaths of Migrants at the Maritime Frontier of the EU”, in Forensic Architecture (ed.), Forensis: The Architecture of Public Truth, Berlin, Sternberg Press, 2014. |

| ↑7 | Nicholas De Genova, “Spectacles of migrant ‘illegality’”, p. 1183. |

| ↑8 | Cp. Maurice Stierl, “A Sea of Struggle – Activist Border Interventions in the Mediterranean Sea”, Citizenship Studies, 20(5), 2016, pp. 561–578. |

| ↑9 | William Walters, “Foucault and frontiers: notes on the birth of the humanitarian border”, in: Ulrich Bröckling, Susanne Krasmann and Thomas Lemke (eds.), Governmentality: Current Issues and Future Challenges, New York, Routledge, 2011, pp. 138–164. |

| ↑10 | See in particular the database established by UNITED and the maps produced by Migreurop based upon them. |

| ↑11 | For our reconstruction of these events, see our report: Charles Heller, Lorenzo Pezzani, and Situ Studio, “Forensic Oceanography. Report on the ‘Left-To-Die Boat’”, Forensic Architecture, 2011. Available at: www.forensic-architecture.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/FO-report.pdf [accessed June 10, 2017]. Our video animation Liquid Traces summarises our findings. |

| ↑12 | Cp. fidh, “63 migrants morts en Méditerranée: des survivants poursuivent leur quête de justice”, fidh, June 18, 2013. Available at: https://www.fidh.org/La-Federation-internationale-des-ligues-des-droits-de-l-homme/droits-des-migrants/63-migrants-morts-en-mediterranee-des-survivants-poursuivent-leur-13483 [accessed June 10, 2017]. |

| ↑13 | Lorenzo Pezzani, and Charles Heller, “A disobedient gaze: strategic interventions in the knowledge(s) of maritime borders”, Postcolonial Studies, 16(3), 2013, pp. 289–298, here: p. 294 (emphasis in original). |

| ↑14 | William Walters, “Migration, vehicles, and politics: Three theses on viapolitics”, European Journal of Social Theory, 18(4), 2015, pp. 469–488, here: p. 481. |

| ↑15 | Cp. Watch the Med, “Over 200 die after shooting by Libyan vessel and delay in rescue”, Watch the Med, 2013. Available at: http://watchthemed.net/reports/view/32 [accessed January 8, 2017]. |

| ↑16 | Cp. Samuel Osborne, “Horrific phone calls reveal how Italian Coast Guard let dozens of refugees drown”, Independent, May 8, 2017. Available at: http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/italian-navy-lets-refugees-drown-migrants-crisis-asylum-seekers-mediterranean-sea-a7724156.html [accessed June 10, 2017]. |

| ↑17 | Cp. Watch the Med, “Guardia Civil runs over refugee boat near Lanzarote”, Watch the Med, 2012. Available at: http://watchthemed.net/index.php/reports/view/33 [accessed May 23, 2015]. |

| ↑18 | For a discussion of the connection with the underground railway of anti-slavery within migrants’ rights activists discourse, see: Welcome to Europe Network, “From Abolitionism to Freedom of Movement? History and Visions of Antiracist Struggles”, Noborder lasts forever, Frankfurt am Main, 2010. Available at: http://conference.w2eu.net/files/2010/11/abolitionism.pdf [accessed June 10, 2017]. |

| ↑19 | Dimitris Papadopoulos, Niamh Stephenson, and Vassilis Tsianos, Escape Routes: Control and Subversion in the 21st Century, London, Pluto Press, 2008. |

| ↑20 | Angela Mitropoulos and Brett Neilson, “Exceptional Times, Non-Governmental Spacings, and Impolitical Movements”, Vacarme, January 8, 2006. Available at: http://www.vacarme.org/article484.html [accessed June 10, 2017]. |

| ↑21 | Cp. Watch the Med, “Safety at Sea. Instructions for a Distress Call”, Watch the Med. Available at: http://watchthemed.net/index.php/page/index/10 [accessed May 23, 2015]. |

| ↑22 | Medhi Alioua and Charles Heller, “Transnational Migration, Clandestinity and Globalization: The Case of Sub- Saharan Transmigrants in Morocco”, in: Gerlinde Vogl, Susanne Witzgall, and Sven Kesselring (eds.), New Mobilities Regimes in Art and Social Sciences, Farnham, Ashgate, 2013, pp. 175–84. |

| ↑23 | Dimitris Papadopoulos and Vassilis S. Tsianos, “After Citizenship: Autonomy of Migration, Organisational Ontology and Mobile Commons”, Citizenship Studies, 17(2), 2013, pp. 178–196, here: p. 190; see also Ilker Ataç, Kim Rygiel, and Maurice Stierl, “The Contentious Politics of Refugee and Migrant Protest and Solidarity Movements: Remaking Citizenship from the Margins”, Citizenship Studies, 20(5), 2016, pp. 527–544. |

| ↑24 | Cp. Alarm Phone, Official Website. Available at: http://alarmphone.org/ [accessed June 10, 2017]. |

| ↑25 | Cp. WatchTheMed, “WatchTheMed Alarm Phone denounces illegal push-back operation with Frontex present”, Watch the Med. Alarmphone, 2016. Available at: https://alarmphone.org/en/2016/06/15/watchthemed-alarm-phone-denounces-illegal-push-back-operation-with-frontex-present/?post_type_release_type=post [accessed January 8, 2017]; see also: Maurice Stierl, “Every refugee boat a rebellion? Supporting border transgressions at sea”, Open Democracy, September 18, 2016. Available at: https://opendemocracy.net/maurice-stierl/every-refugee-boat-rebellion-supporting-border-transgressions-at-s [accessed January 8, 2017]. |

| ↑26 | Andoni Alonso, and Pedro J. Oiarzabal, Diasporas in the New Media Age, Reno, University of Nevada Press, 2010, p. 5. |

| ↑27 | Maurice Stierl, “A Sea of Struggle”, p. 561. |

| ↑28 | We have detailed this policy shift and its effects in our report deathbyrescue.org. |

| ↑29 | Maurice Stierl, “A Fleet of Mediterranean Border Humanitarians”, Antipode, 2017. Available at: doi: 10.1111/anti.12320 [accessed June 10, 2017]. |

| ↑30 | Quoted in Silja Klepp, “A Contested Asylum System: The European Union between Refugee Protection and Border Control in the Mediterranean Sea”, European Journal of Migration and Law, 12, 2010, pp. 1–21. |

| ↑31 | See for example Eyal Weizman, Hollow Land: Israel’s Architecture of Occupation, London, Verso, 2007. |

| ↑32 | Cp. Paolo Cuttitta, “Le monde-frontière. Le contrôle de l’immigration dans l’espace globalise”, Cultures & Conflits, 68, 2007, pp. 61–84. |

| ↑33 | Cp. Saskia Sassen, Territory, Authority, Rights: From Medieval to Global Assemblages, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2006. See also Philip E. Steinberg, “Lines of Division, Lines of Connection: Stewardship in the World Ocean”, Geographical Review, 89(2), 1999, pp. 254–264 and Philip E. Steinberg, “Free sea”, in: Stephen Legg (ed.), Spatiality, Sovereignty and Carl Schmitt: Geographies of the Nomos, London, Routledge, 2011, pp. 268–275. |

| ↑34 | Brett Neilson, “Between Governance and Sovereignty: Remaking the Borderscape to Australia’s North”, Local-Global Journal, 8, 2010: pp. 124–140, here: p. 126. Available at: http://mams.rmit.edu.au/56k3qh2kfcx1.pdf [accessed June 10, 2017]. |

| ↑35 | Cp. Philip E. Steinberg, The Social Construction of the Ocean, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2001; Thomas Gammeltoft-Hansen and Tanja E. Alberts, “Sovereignty at Sea: The Law and Politics of Saving Lives in the Mare Liberum”, DIIS Working Paper 18, 2010; Juan Luis Suárez de Vivero, Jurisdictional Waters in the Mediterranean and Black Seas, Bruxelles, European Parliament, 2010. |

| ↑36 | Étienne Balibar, We, the People of Europe? Reflections on Transnational Citizenship, Princeton, University Press, 2004, p. 109. |

Charles Heller is a researcher and filmmaker whose work has a long-standing focus on the politics of migration. In 2015, he completed a Ph.D. in Research Architecture at Goldsmiths, University of London, where he continues to be affiliated as a research fellow. He is currently based in Cairo, conducting a postdoctoral research supported by the Swiss National Fund (SNF) at the Centre for Migration and Refugee Studies, American University, Cairo and the Centre d’Etudes et de Documentation Economiques, Juridiques et Sociales, Cairo. Together with Lorenzo Pezzani, with whom he has collaborated since 2011, they co-founded the WatchTheMed Platform and have been working on Forensic Oceanography, a project that critically investigates the militarized border regime and the politics of migration in the Mediterranean Sea. Their collaborative work has been exhibited internationally and has been published in several edited volumes as well as in the journals Cultural Studies, Postcolonial Studies, and in the Revue Européenne des Migrations Internationales.

Lorenzo Pezzani is an architect and researcher. He is currently Lecturer at Goldsmiths, University of London, where he leads the MA studio in Forensic Architecture. His work deals with the spatial politics and visual cultures of migration, with a particular focus on the geography of the ocean. Since 2011, he has been working on Forensic Oceanography and other collaborative projects that critically investigate the militarized border regime in the Mediterranean Sea. Together with a wide network of NGOs, scientists, journalists, and activist groups, he has produced maps, videos and human right reports that attempt to document and challenge the continuing death of migrants at sea.

Dr. Maurice Stierl is Visiting Assistant Professor in Comparative Border Studies at the University of California, Davis and is associated with Cultural Studies and African American/African Studies. His research focuses on migration and border struggles in contemporary Europe and is broadly situated in the disciplines of International Relations, International Political Sociology, and Migration, Citizenship & Border Studies. His work has appeared in the journals Antipode, Globalizations, Citizenship Studies, Movements, Global Society, and elsewhere. Dr Stierl is a member of the activist project WatchTheMed Alarm Phone and the research collectives Kritnet, MobLab, and Authority & Political Technologies.